Applied Philosophy or: How I Learned to Stop Theorizing and Love Mechanisms

The philosophers of tomorrow will test their theories in code.

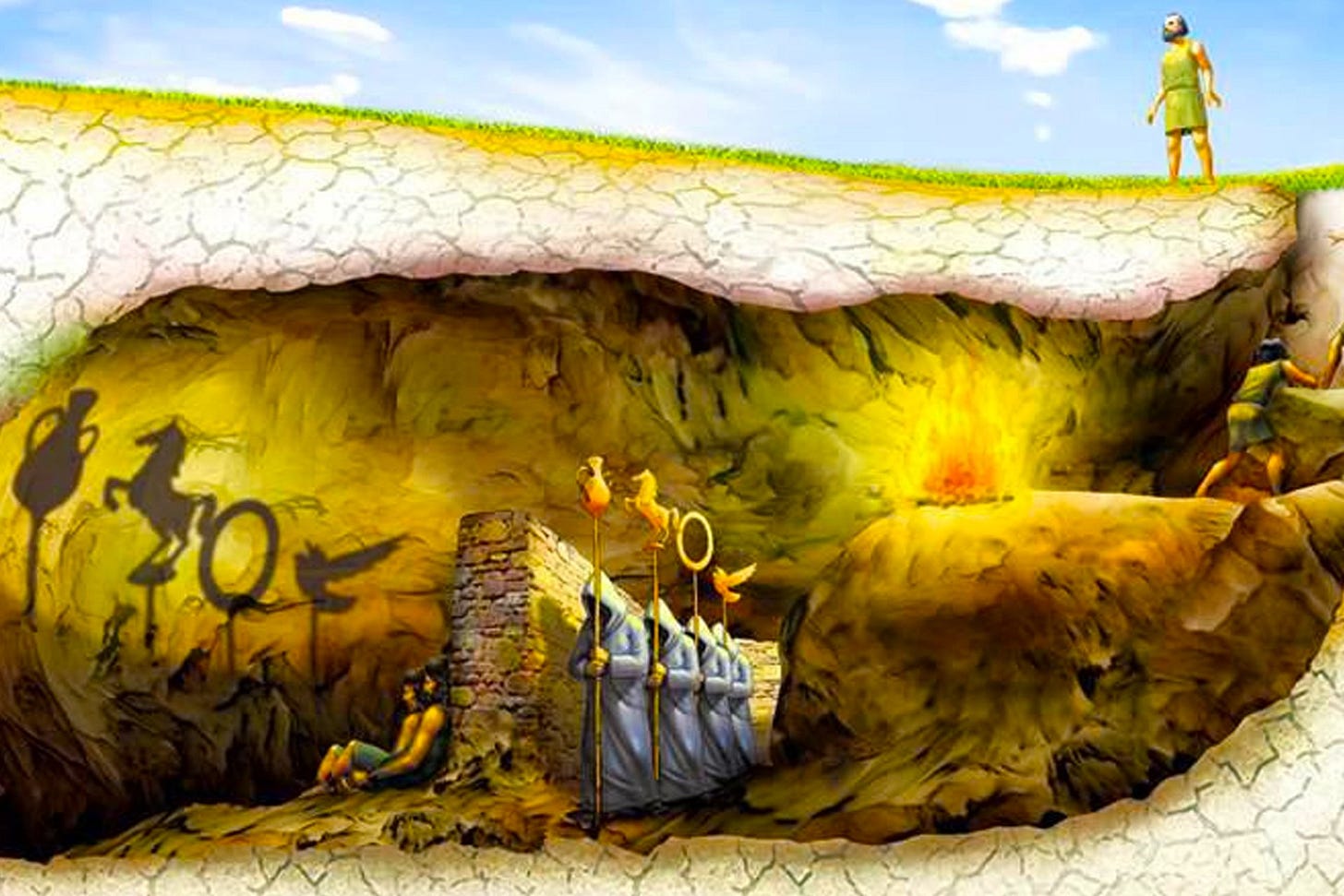

Philosophers since antiquity have made their money by coming up with theories of value, knowledge, and morality. They have then used these theories to construct thought experiments or scenarios in which the basic tenets of the theories could be pushed to their limits. This makes for great intellectual fun, along with mind-bending paradoxes that tell us a little bit about who we are. These experiments look like:

or:

or:

or:

The curious thing about all of these is that they are structures constructed in abstract terms, but whose intended purpose is to tell us about how to concretely live our lives. Consider the trolley problem, which has been the subject of great discussion since the advent of autonomous cars. On one hand, it is a purely philsophical problem. When are five people going to be tied up to a train track with one other person tied to another track (and you have to press the button)? It’s a ludicrous proposition.

On the other hand, we seemingly make such ethical and moral tradeoffs all the time. They are not phrased as trolley problems, but human values are deeply tied to our inability to simultaneously choose between two morally good options at the same time. The trolley problem then seeks to formalize our inability to ethically “double-spend”.

However, the big problem with these thought experiments (and the thousands of pages that have been subsequently written about them) is that they don’t shine any light on what humans would actually do if faced with such tradeoffs. That is the realm of markets.

Markets are the places where humans actually express their values (and reveal what their preferences are). For a long time, most markets were informal and open-air. This is a typical view of a market throughout history:

Buyers and sellers would congregate in one place and quote prices to each other. The sellers would try to maximize their take-home profit and clear their produce for the day. The buyers would try to get the best goods and prices subject to what they could spend.

As markets became more sophisticated, however, the job of quoting prices became too difficult for any individual human to do, and we shifted to using electronic systems, firms, and technology to do this. The structure of how the market functions, however, was decided by a few authorities whose job it was to regulate the market (formally called market microstructure). This job answers questions like: Who is allowed to buy and sell? What kind of products can be sold? How are prices formed and discovered?

Recently, with the advent of crypto markets in which particular microstructure designs can be implemented in code almost instantaneously, we have seen an explosion of systems that govern human exchange. These include automated market makers or exchanges like Uniswap, Balancer, or Osmosis where users can go and trade crypto tokens with an automated system in the backend deciding prices. Users are trading tens of billions of dollars of value on these exchanges. In this brave new crypto world, there are also reserve currencies, lending platforms, and games.

All of these are examples of mechanisms. That is, they are programs that function by setting economic incentives among humans on the platform. Designing mechanisms has been popular in economics for many years. What’s new is our ability to deploy them instantly and test them.

Market microstructure, and generally, the problem of market design maps quite neatly onto the philosopher’s desire to run thought experiments regarding human values and moral preferences. Philosophers would like to have controlled arenas to run tests about human judgment. However, till now, they have not had access to realistic test environments where humans actually express their true preferences subject to incentives.

I therefore argue that the future of philosophy is philosophy that is tested in mechanisms. That is, philosophers who want to understand particular aspects of human values and ethics will find tremedous utility in designing market mechanisms to do theory-testing. Philosophers will code up their favorite mechanism for organizing humans/information and test it in reality rather than building theory towers to nowhere.

These mechanisms will likely be deployed on decentralized systems. There is a program of tremendous research potential available here. Maybe this should be called mechanistic philosophy (the meeting of market design and philosophy).

I therefore lay down here the fundamental dogma of mechanistic philosophy: human morality is whatever humans do when faced with actual tradeoffs about actual things they care about. Everything else is theorizing.

It follows as a corollary that if we are interested in understanding (or improving) human morality, we should create markets that allow humans to express their preferences and then use information from these markets to iteratively design better mechanisms that disincentivize “bad” behavior and reward “good” behavior.

We’re at the tipping point of a revolution in philosophy and our understanding of ourselves. Money, value, and morality become one when it is possible for designers to create markets that elicit particular kinds of behavior. What will be the difference between a philosopher and a programmer? It’s an exciting world we are heading into.